The science fiction in games and other entertainment used to be very different from real-life technology. Sci-fi creators made time machines and flying cars. But increasingly, we see the creative visions of plausible science fiction becoming the inspiration for real-life technology and video games. And visa versa. We have deep learning neural networks and smart A.I. and self-driving cars. The head of Japan’s SoftBank just bought ARM for $32 billion in a bid to create the Singularity, or the day when A.I. becomes smarter than humans.

“The science fiction in games and other entertainment used to be very different from real-life technology.”

Novels such as Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash inspired Silicon Valley’s virtual worlds, like Second Life. Blade Runner, The Matrix, Minority Report, Inception, Black Mirror, Ex Machina, and HBO’s new remake of Westworld have also inspired new visions for technology companies and new plots for video game stories. Sci-fi and video games are a mirror for our own times.

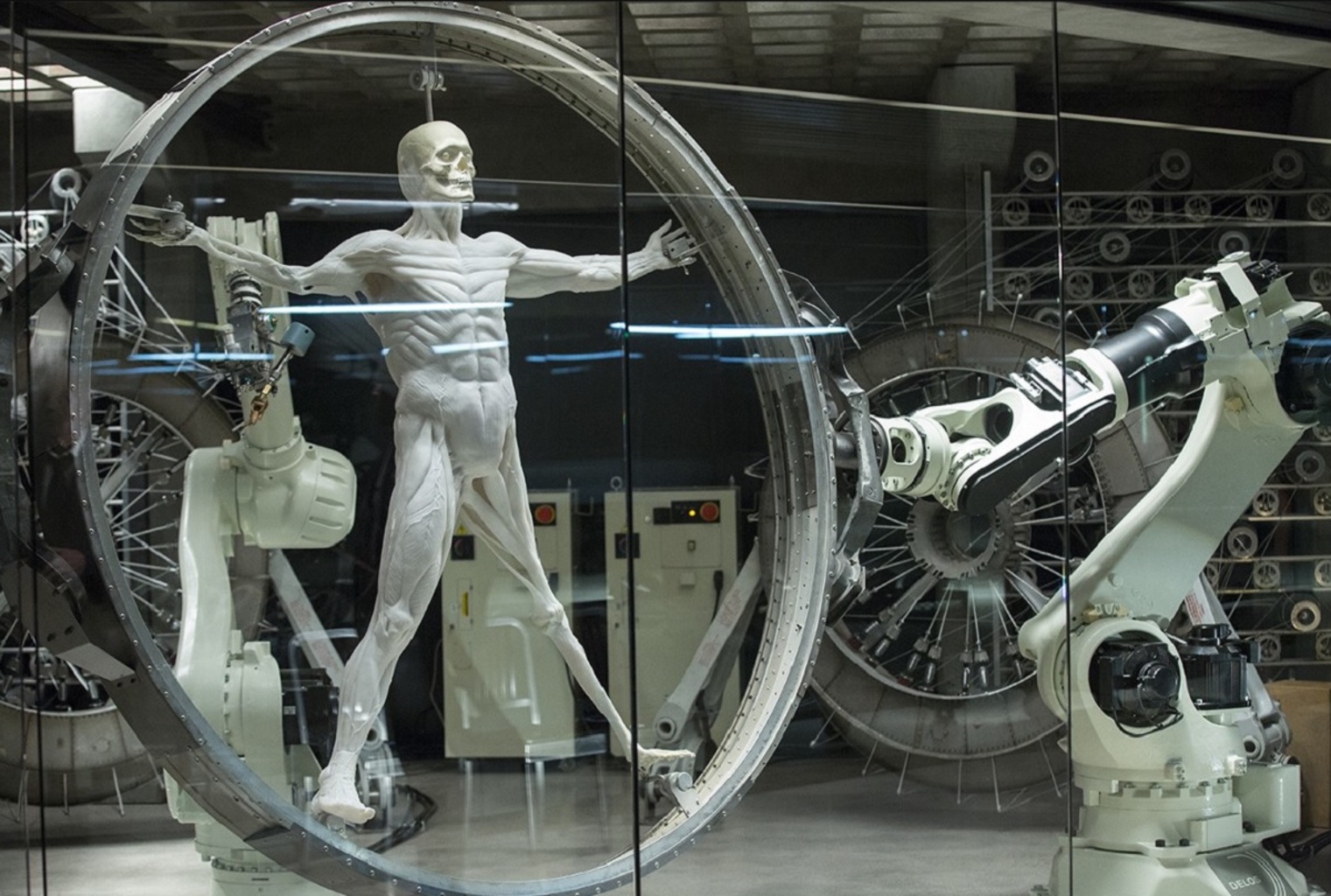

Video games, science fiction, and real-world technology are in a positive and accelerating inspiration cycle. Square Enix’s Deus Ex: Mankind Divided has a tight connection with the real world. The company Open Bionics is creating 3D-printed artificial limbs inspired by the arm of Adam Jensen, the hero in Deus Ex, where “natural humans” and “augmented humans” come into conflict.

We’ve also seen Ubisoft’s Watch Dogs 2 game show the same kind of close ties to the real world, as the game focuses on the hacktivists of San Francisco and their bid to hack into smart cities. Those smart cities are being championed by all sorts of tech companies, but the makers of Watch Dogs are offering a warning about moving too fast into smart city services without thinking through the consequences of security vulnerabilities.

At the recent Montreal International Game Summit, I moderated a panel on the connection and inspiration happening between games, sci-fi, and real world tech.

My panelists included:

-

Jonathan Morin, creative director at Ubisoft Montreal and a key leader on Watch Dogs 2;

-

Sebastian Alvarado, cofounder of Thwacke Consulting, science advisor for video games; and

-

Andre Vu, executive brand director for the Deus Ex franchise at Eidos Montreal.

Here’s an edited transcript of our conversation.

This subject, by the way, will be one of our themes at the GamesBeat Summit 2017 event coming this spring. (Contact me if you want to get involved).

Sebastian Alvarado: I’m co-founder and CEO of Thwacke Consulting. I’m also a scientist. I currently work at Stanford University. I’m a molecular biologist. I became a molecular biologist because I wanted to make the X-Men. [laughs] I learned very quickly I couldn’t do that, but learned a lot of other things too. I did my PhD here at McGill in Montreal. As I was in Montreal, I playtested at lots of studios here. I found myself getting close to the video game industry.

One day I saw a writer Wikipedia’ing DNA, and I thought that was a good opportunity, so we started our group. Since then we’ve worked with a bunch of indies in Montreal, but also abroad as well. We’re now consulting science with the entertainment sector more broadly. Some notable clients are Marvel Entertainment. We helped build their super-soldier serum and explain how the Hulk transforms himself for a museum exhibit in Times Square and Las Vegas. We’ve worked with Warner Bros. Games and a handful of other triple-A companies.

I’m a geneticist and molecular biologist by training. My expertise in science fiction usually relates to refreshing the trope of “his DNA makes him the chosen one.” I’ve gotten pretty tired of that one, but I’ve done what I can to reinvigorate it with a lot of science that’s been bleeding-edge in the lab.

GamesBeat: You got to work with Will Rosellini (the science consultant for Deus Ex: Mankind Divided).

Alvarado: When I first started Thwacke I wanted to reach out to people who’d done science consulting for the game industry. I reached out to him. We’ve been in touch since then, for a few years.

Jonathan Morin: I’m creative director on Watch Dogs and Watch Dogs 2. I work at Ubisoft. The video game industry is an eclectic beast. We all have different backgrounds. I was supposed to become a math teacher, which was a lot more formal and redundant. Progressively, while I was learning science and math, I stumbled on the realization that people could make games for a job. So I switched slightly and decided to study 3D animation and programming. That got me here.

Ironically, now I make games that talk about programming and hacking and the connecting world. I went from one kind of math to another, to a certain extent.

Andre Vu: I’m executive brand director on the Deus Ex franchise. I used to work with Jonathan, more than—almost 10 years ago, on Far Cry 2. We decided to take a bunch of crazy people to revive the Deus Ex franchise. It was very inspiring in terms of gameplay, but also with its themes. We wanted to have a better approach in a sense that—we wanted to make it more relatable and more modern for today’s audience. We consulted with Will Rosellini as well. That was very interesting, almost 10 years ago.

“Ironically, now I make games that talk about programming and hacking and the connecting world.”

GamesBeat: Do all video game stories start from some kind of non-fiction before you start fictionalizing them?

Morin: In my case, it couldn’t be more true. Watch Dogs, the first game, started with 10 people around a table drinking beer and talking about the impact of smartphones. The first smartphone had just come out, the first Apple iPhone. Of course we all had one. We’re kind of a cage full of geeks up there, a lot of early adopters of technology. But my brother and my mother and most other people didn’t know what the hell a smartphone was.

We were fascinated by the impact of this thing. What would happen if we all had Facebook in our pocket, in every place and at every moment? It was obvious that intellectually and creatively we were interested in what that would mean, and that’s where Watch Dogs was born. It starts with what we’re interested in.

GamesBeat: Within days of when it came out, it had been hacked.

Morin: Exactly as you’d expect. To me, people need to have some form of fascination with something to create. Very rarely is it going to be completely without reference. For us it that impact, this society-changing moment where technology would now be sitting there with your keys and your wallet. It used to be that your keys and your wallet were the two things you always kept with you. Now your phone is with you too, a computer and everything connected to it. A lot of things are with you all the time now. That raised a lot of questions to explore.

GamesBeat: As you’re designing this in real time, though, you’re also seeing the hacking of smartphones come along.

Morin: Right. It was obvious, every flaw we’d read about. But for it was less about what was hackable, because everything is hackable. What was interesting was putting up the mirror to people and their relationship with technology. There were lots of fun videos on YouTube of stunts — I remember one where people were spying on a team of people on Facebook, as if they were behind a curtain, watching people telling each other about their lives. It was just stuff people were telling the world through Facebook. Watch Dogs touched on that a bit.

A lot of people said to me afterward that it changed their relationship with technology, because seeing all this information about everybody on the streets got them thinking. It’s kind of creepy. You don’t want to know so much about people. They’d say, “Suddenly it’s impossible to do the kinds of things to them that you’d usually do in a game.”

In the second game now — everything you can hack in the game, it’s completely doable in reality. It’s harder to do. It takes a bit more effort. But all of these things — journalists have gone through and said to me, “You’re right, this is all possible.” Technology has become exponentially more powerful.

GamesBeat: Have any predictions or propositions in the story of Watch Dogs come true?

Morin: A lot of things have happened. In the first game, we used data systems to open prison doors. A guy at DefCon demonstrated the same bug that StuxNet exploited—it could be used to simultaneously open up cells in several different prisons in the United States. Those places are fascinating, because hackers are the first ones to pick up on potential problems. Two or three years later, those problems emerge in the wider world.

We talk to hackers every day and consult with these guys. We ended up realizing how efficient they are. At the beginning of the game, you start out by backing into a stadium and creating a blackout. I think two weeks after we brainstormed that idea, there was a blackout at a football game. It became a bit uncanny, to say the least. We got accustomed to revealing stuff about Watch Dogs and seeing the same things in the headlines. There wasn’t any magic behind that. It just happened.

Edward Snowden ended up making the news I think two days before we revealed Watch Dogs at E3, which was very weird. We revealed Watch Dogs 2 in the middle of all this controversy about Trump and hacking and social media. The story we decided to pitch at E3 was about the impact of social media on democracy. It’s so in line that it feels like if we actively tried to avoid it, we’d fail.

GamesBeat: Deus Ex came out of the 1990s, but you rebooted it in a way that more closely tied it to the present day and things that are currently happening.

Vu: What was interesting for us when we started Human Revolution was taking what made it a good game first. But beyond that, it was about telling a story, a human story, what it means to be human when you have these kinds of advanced technology. How does it affect people, these disruptive technologies? The internet is just one of them.

We mixed those themes with the sense of — the first Deus Ex was all about nanotechnology. That’s something you can’t really see. It was more interesting to reward players with something more noticeable. Mechanical augmentation worked for that. We went back and wrote a new story in order to give people a clearer understand of where we’re going in a few years. It was set in 2027. Today we’re almost in 2017.

And we were very interested in the work at Open Bionics. It started, actually, when they were pinged by some of our fans — “Have you seen what the Deus Ex team is talking about?” While on our side we had people who’d been inspired by the original Deus Ex to jump into scientific fields. They told us, “You should definitely talk with these guys.” We were promoting the same ideas, in some way.

GamesBeat: You had something I’d never heard of in a game before, a science advisor, Will Rosellini. He was a big fan of the game, and he came along to give a lot of explanations for how this could be real.

Vu: Absolutely. It was very funny. He’s a huge fan of the first Deus Ex games. He heard about the reboot back in the day and contacted us. I remember getting his email. “Guys, I love the game and I’ll be here in Montreal. Can we talk?” We started to discuss things with him. He says, “I’d love to help you and bring more accurate scientific detail to the game.” We jumped on the chance to work with him. We were already working with the Open Bionics conference in New York, putting that technology at the forefront, and we had some guys who’d gotten into the field because they’d played Human Revolution.

GamesBeat: And Will, while he’s been consulting with you, has also been trying to make human augmentation happen for real.

Vu: Absolutely. We believe that this isn’t just a joke or a fantasy. It’s really happening. In 2016 we’re already catching up with what we tried to create for 2027.

“It’s starting to become a lot more interesting for science fiction, because we can take extra leaps forward on the notions science fiction has had for a long time…”

GamesBeat: So, science advisor to video games. That’s Sebastian’s new career. It’s interesting that we’ve come to a point where this is a job that can exist. It used to be that science fiction was so far out that you didn’t need a connection to real science. Now it’s all about things that can happen.

Alvarado: For me, my adventure went the other way around. From a very young age I was into comic books, Marvel Comics, Wolverine, things like that, and I wanted to do science so I could find the X-gene and turn it on and become a mutant. That was when I was seven or eight years old. [laughs]

Then I found myself on the career path of an academic, going to do my PhD. It was just a stroke of luck, doing my doctorate at McGill and being close to all these development studios like Ubisoft and playtesting to get free games because I was a poor graduate student. It was a unique opportunity, being in the right time and the right place, and realizing that when you do this much time doing basic research, you’re at the forefront of technology. You’re the thinker, developing the ideas that have not even gotten into textbooks yet.

When you’re in that space, you know what’s possible and what’s not. But you also know what’s speculative in terms of science. You can draw your way to a certain outcome – “If I do this experiment, I can find out the answer to that.” It’s starting to become a lot more interesting for science fiction, because we can take extra leaps forward on the notions science fiction has had for a long time and say, “Well, if we test this based on what we already know, we’re grounded in plausibility. This is a reasonable experiment to do. What if it works?” We find ourselves doing these experiments and they actually work.

I can talk about my own work. I’ve shrunk and enlarged ants. I pitched that to Marvel and got feedback from Kevin Feige off that story. Now, if I told you I could shrink and enlarge ants, you’d tell me I was a crackpot. But I published the paper. This is real science. When it made headlines, it was based on real work.

Even to this day, there are things like optogenetics. You may not hear about it, but Stanford University has Karl Deisseroth. He developed this technique that allows you to turn on individual neurons in a mouse’s brain, based on shooting different wavelengths of light at it. With a fiber optic cable or an RFID, you can shoot blue light, red light, and turn on individual groups of neurons and control behavior with it. That starts to travel into all these science fiction ideas about mind control and things like that.

GamesBeat: In the CNN documentary that Deus Ex was part of, they had a lot of people with artificial limbs. It was very interesting, and very moving as well. But it also some stranger ideas, like one man who wanted to be the first wired human, connecting his brain to something. I have trouble accepting some of these.

Vu: That’s a bit of an extreme. Not everyone wants to wire their brain. But if the technology is available, someone will do it. What’s important for Deus Ex is showcasing what could happen. We’re not taking a side. It’s important for us that the player gets to choose what side they want to be on based on their own knowledge and their own background.

But yeah, we met this guy. It’s an interesting approach. It’s his way of expressing himself. Who am I to tell him it’s not right? Everyone has their own reasons. Some people have lost limbs and want to get back what they had. Some people want to extend the possibilities of what they can do. It’s not that far-fetched anymore. Oscar Pistorius, for example, the Olympic runner. We originally considered a similar story for the Deus Ex lore. What if someone on blades could run faster than anyone? Would they let him in the Olympics? Two years later it happened.

You get to a point where things are difficult to control. It’s like I said about disruptive technology. People will do what they want with it. Governments and others will try to control it, but–

“Not everyone wants to wire their brain. But if the technology is available, someone will do it.”

GamesBeat: Because you’re working fiction, you can go places that a lot of technologists don’t. They work on their technology and try to make it happen. They don’t necessarily consider ethical implications, the consequences of how technology might go wrong. But in fiction you think about that more often.

Vu: Right. We try to see different cases, in biotech or whatever. We try to guess where things might go. We don’t take just one side. We try to offer a full spectrum of what might happen. When you brainstorm, you have a lot of intelligent people thinking around a theme. Everyone has their own experience and everyone can stretch to a certain extreme. It’s important to explore all these different possibilities, because what you might want to do with technology and what I’d do could be very different.

GamesBeat: In your game, I thought it was interesting that you’d predict people cutting their own arms off to replace it with a new one.

Vu: Well, we already have people coming up with different kinds of extensions to their own bodies. Will Rosellini has talked about people using NFC chips and so on. That’s just the start. If your limb has some defect, maybe, why not replace it with something ten times better?

GamesBeat: And that leads you to your conflict between natural and augmented people, with political scapegoating happening to marginalize people. That’s the heart of what makes the story interesting.

Vu: We got to know Tilly Lockey, a woman who lost both arms. She’s now using a prototype of Adam Jensen’s arm. When people see that, instead of seeing her as diminished, everyone says it’s super cool. It’s customizable. You could do whatever you wanted with something like that. It’s not totally far-fetched to consider that someday someone’s going to say, “Hey, instead of having a new iPhone, I’ll get a new arm.”

For younger people it’s easier, maybe. It starts with tattoos and other little modifications. But you can extrapolate that to something big. It’s natural. Kids these days are more extreme, more stimulated in a lot of ways. The internet creates so much more awareness. They’ll seek extremes in everything, in ways of expressing themselves. It’s fascinating. It’s cool to explore these things in a more grand way. It shakes our way of thinking sometimes. But it’s great. I wouldn’t be surprised to see people saying, “My arm is cooler than yours. Look at the design on it.” Think of a guy who’s really good at painting figures for board games. He could end up being the best custom arm painter in the world. Why not?

“The thing about smart cities is, how can you secure something that isn’t just one product? A smart city isn’t a product. A smart city is an OS, an infrastructure of computers.”

GamesBeat: Watch Dogs looked at the down sides of smart cities. These are things that the companies pushing smart cities don’t talk about a lot. They say their systems are secure, but that’s what you’d expect them to say. From the research you’ve done, do you believe that this could still be a bad idea?

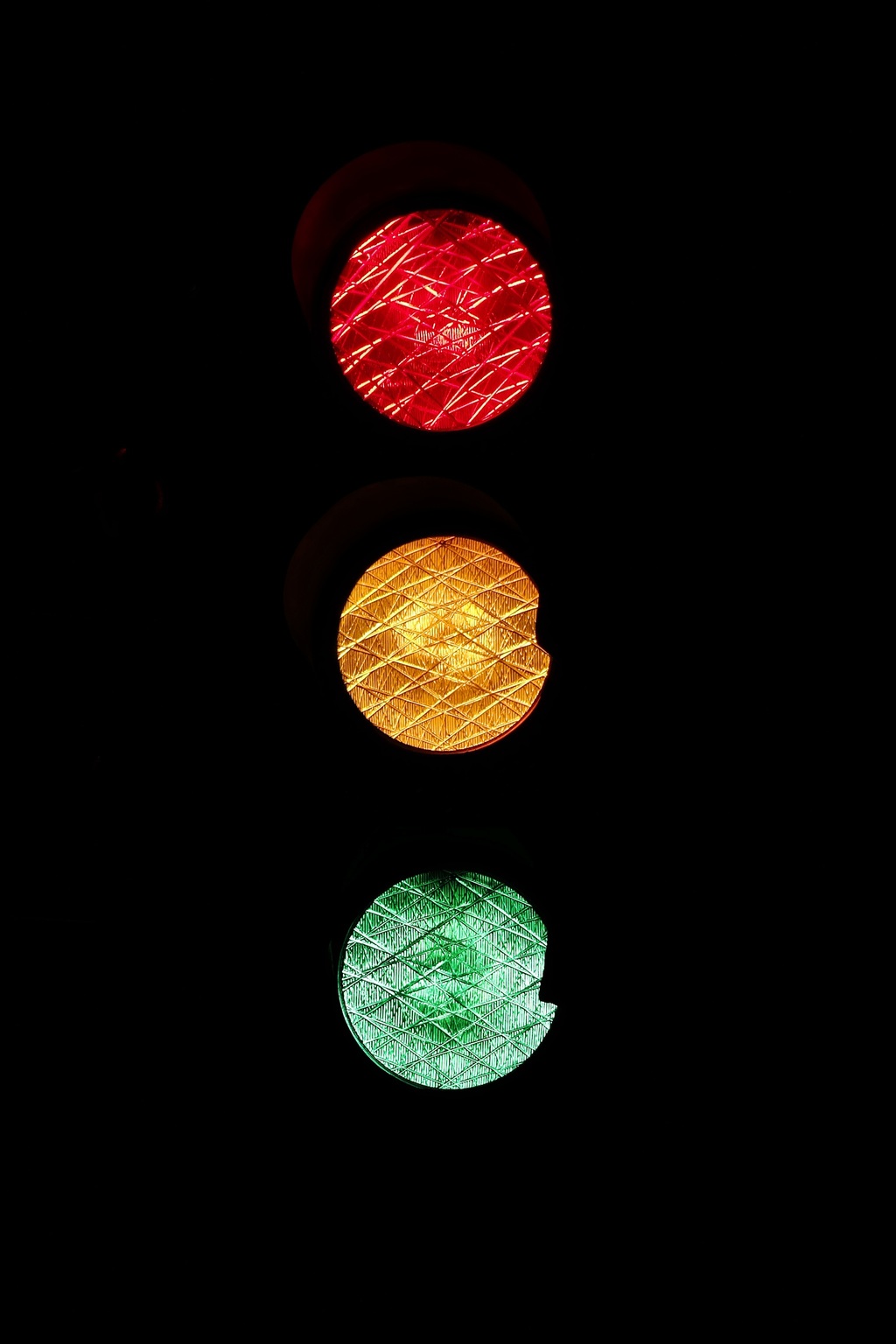

Morin: I’ve never thought smart cities were necessarily a bad idea by design. The thing is — just go to DefCon once, through this swarm of conferences, and you’ll realize what’s going on. Every time you’re sitting in a room at DefCon, they’ll start demonstrating whatever they want to do. Always, every single conversation, there’s this moment where they go — I remember one where a guy demonstrated how a certain system for traffic lights could be hacked. I was interested in that because we were exploring the same idea for the game. He had his backpack and his laptop, he’s pointing at an intersection in I forget which U.S. city, and suddenly he’s connected to every traffic light and controlling them. With his laptop.

Right there he called up the company that made the sensor for these traffic signals. “Hey, your product says it’s encrypted, but it’s not.” Everyone in the room starts laughing. It’s a running joke with these guys. Companies always say, “Sure, it’s encrypted,” and 99 percent of the time it’s either poorly done or not done at all. In this case it wasn’t encrypted at all. Open to connections.

So the guy on the other end says, “No, it’s encrypted,” arguing on the phone. Then he calls again and gets one level up in management, again and again. Eventually he gets a response. “Yeah, we did focus groups, and the connection was too slow with the encryption. It was a better product without it.” You focus-grouped security? And they kept claiming it was encrypted anyway. Of course the people in the cities that bought the product didn’t test it enough to notice. They just installed it. And that’s why DefCon exists. People go there and show off these things and they all find it really funny.

The thing about smart cities is, how can you secure something that isn’t just one product? A smart city isn’t a product. A smart city is an OS, an infrastructure of computers. You look back at the DDoS attack a couple of weeks ago, it’s a similar problem. All these things are connected to the internet. If one of those things is flawed — and all of them are different products from different companies, some of them that aren’t that great – the whole thing is flawed. Someone can get into the entire infrastructure and control the entire thing.

I feel like every time we create a game or a story or a universe, we want it to be relatable. A good way to make it relatable is to make people think about their own lives.

GamesBeat: All these things that are hackable, that’s the grain of truth in Watch Dogs. The part where it turns to fiction, maybe, is how seamlessly everything is connected and how quickly you can do a hack.

Morin: Yeah, the fiction is in how easy it is to connect to everything. But seamlessly connecting to everything, that’s closer and closer to reality. We’re making an extrapolation to a couple of years off. But often our initial conceptions end up being 80 percent reality once we ship. The speed at which this is all going is crazy. There are stories of products where, if you start extrapolating, people get scared.

GamesBeat: About six billion things are connected to the internet?

Morin: Right. And that’s growing fast. People don’t understand. They buy a camera to keep an eye on their kids — cool, right? I’ve been with my friends when they’re watching their kids on their phone with the camera while they’re on a trip. Me, I just think, there have been tons of hacks with those things. Personally it doesn’t make me feel safe. And that’s just one product. Maybe the flaw isn’t there. Maybe it’s your router. Everything that’s on the internet is connected, and most of the time they don’t sell you that part of the story.

“The speed at which this is all going is crazy. There are stories of products where, if you start extrapolating, people get scared.”

By: Dean Takahashi (@DEANTAK)

NOVEMBER 23, 2016 7:00 AM

Disclosure: The organizers of MIGS 2016 paid my way to Montreal. Our coverage remains objective.